Art and Grief

Bethany Tobin

In this interview titled Art and Grief, I asked Bethany Tobin to tell us her story of finding healing in painting her emotional response to a Thai woman's story. I first met Bethany when she was a teenager living in Thailand. Her family lived there for many years, so Bethany was very familiar with Thai culture and society.

Bethany was always one to have art supplies close at hand. Her undergrad degree was in art. You can see more of her work, including more images from her project on Sombong's story at bethanytobin.com. First tell us Sombong’s story.

Sombong was born to a poor Thai family. Her parents separated when she was small, and she grew up with her father and step mother. From an early age Sombong worked in a factory and brought home her wages to help with family expenses. She said that growing up she only owned the shirt on her back. One poignant early childhood memory she recounted to my family was that one time her half brothers and sisters were taunting her and teasing her. She appealed to her father for help. Instead of defending her, he callously threatened her to shut up by flashing a knife. She said that in that moment something died inside her. She knew she had no one to speak for her. When she was 13 years old Sombong’s family sold her as a “house-helper” to a Chinese man in Bangkok, but it was no secret that Sombong was going to be used as a sex slave. After a long time, she found her way out of that situation, but there weren't many opportunities open to her and returning home was not an option. So she worked as a prostitute, all the time sending her wages back home. Within a few years she became ill. By the time she was in her early twenties, she became too ill to work and was literally dying. She returned to the village in Det Udom, to her family. Now stigmatized by AIDS, she was put in the back room of their home and neglected. She must have come into the Det Udom hospital at some point because somehow her name was put on the HIV/AIDS support group roster at the hospital. Around the same time, a group of Thai Christian believers who were a part of our church became aware of the numerous families and individuals affected by HIV/AIDS. So many people were coming home from the city to die or had families in the villages that had also contracted the disease and were desperate for help. This group of Christians made a commitment to start visiting AIDS patients on a weekly basis. They partnered with the support group at the hospital and soon befriended Sombong. They cared for her needs, took her to and from the hospital and offered genuine friendship in an otherwise very hostile and discriminating situation. In between hospital and hospice care, she also stayed with my family for some time.

Through contact with Thai believers, Sombong experienced the unconditional love of God. Here was a Father who took up her defense. Here was a group of people that did not shun her and instead reached out in friendship. The experience of church transformed her, and she recognized herself as a child of God. I remember being awed and shocked to hear her say that she had forgiven her family. She spoke those words on a day when her family had to be coerced to drop off some of her clothes for her at the hospital, and when they finally did, had simply dropped the bundle at the door and left. One time when my mom and I visited her at the hospital, we came on her doing jumping jacks. She was so embarrassed and said, "Oh no, you saw me. I must look crazy, like a skeleton bouncing around." But we were impressed by her resilience. Though her body was weakening and she often expressed frustration, Sombong was energetic and motivated. While in the hospital, she wrote letters exposing the corruption of hospital officials who siphoned government aid money designated for HIV/AIDS patients. She also wrote thank you letters to her nurses and dreamed about opening a restaurant. She told me she didn't want to die, and she wasn't ready. But instead of continuing to recover, infections progressively got worse. The last time I saw her in the hospital, there wasn't even space for her in a room. She was alone in a crowded hospital hallway, but a merciful nurse was providing the food, bathing and basic care that is traditionally the family's job in Thai hospitals. Sombong died in February 2002, alone in that crowed hospital hallway. Her family did not give her a funeral.

How did you get started painting to work out your emotions after meeting Sombong?

Hearing Sombong’s story and watching her struggle with dying so young, I started to draw. I was eighteen. I didn’t know what the word “catharsis” meant, and I wasn’t trying to do art therapy. I remember the first time I heard her whole story from my dad. I drew a picture of what it might have been like for her as a prostitute. I drew her sitting on the bed half naked in a dark room now empty. I was completely horrified with myself for wanting to draw this and immediately hid my drawing. A few weeks later I drew something again. It started to dawn on me that since I was an artist, and this was what I was working through, it would come out one way or another. As we continued to spend time together that summer, I kept drawing. I didn't show her my pictures, and she never knew I was doing them. I was simply responding to the fraction of her anger that I could understand and expressing my own feelings of outrage.

What changed for you as you did the paintings?

I returned to school after that summer that I met her. I had to do a final project that year for my art program: An in-depth project on a topic of my choice. I decided to give myself to Sombong's story. It was really helpful for me to decide to spend a whole year intentionally finding ways to express the injustice, outrage and loss in what had happened to Sombong. I focused on putting myself in that story, in researching, in thinking about it and feeling it. In February, half way through the year, while I was at home on Christmas break, Sombong died. So in many ways, throughout that year through my drawing and painting I tried to imagine what was happening to Sombong. The progression of drawings went through the shock of diagnosis, the anger and despair of coming to terms with it, the long painful decline and the final agonizing release. Physically and emotionally, I dwelt there. I remember talking to my mom about her concern for me and this really "dark" work I was doing. She was telling me that I didn't need to stay there forever, and I remember saying that I had to stay to do her life justice. When the summer came again, however, I stopped drawing and did feel ready in some ways to move on. Instead of creating drawings, I wanted to share the drawings and the journey they described.

Of the paintings you choose to share, you can answer some of the following questions: What was happening in you as you were working on the painting? What does the painting mean to you? How did individual paintings contribute to your working through your emotions?

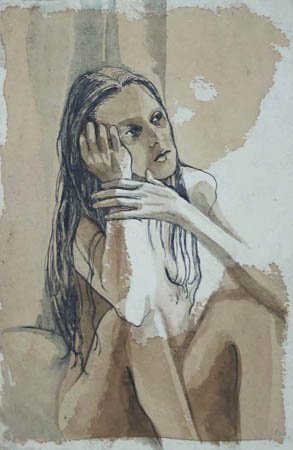

Figure in ink and watercolor. This is one of my earlier pieces which were more about the process of coming to terms with the diagnosis and illness. I wondered if it was a very lonely place, and filled with despair and regret. I thought about how it would be to have to face death so young and to let go of one's dreams for the future.

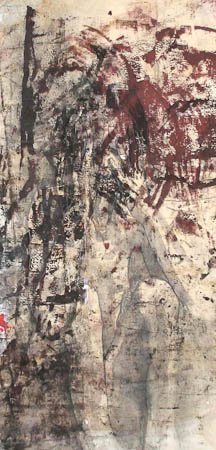

Figure with ink and monotype. Here I am trying to imagine and express the anger and despair in the process of facing death. Maybe the darkness and horror of it all comes rushing on...and times with such fury. I used monotype where you spread ink on a piece of glass and then flip your paper onto it for a one-off print. The ink can squish around and make some very free and random marks. It looks to me like a cloud of darkness hurtling around her head and her hands are raised to protect herself.

Collage. In this piece I was pretty much venting my rage against the injustice that would allow human beings to be used and the discarded as if they were disposable. As if they were commodities. From forced prostitution to deteriorating AIDS patient, was the price of her life? From the blossom of youth to skeletal frame, was there ever a point when society didn't look at her and see her cost? I ripped up paper, slashed graphite across it and scrawled my disgust all over the page. This piece has more kinesthetic connection with raw emotion than the others. It's not the best piece in terms of art, but it's from the gut.

Figure with ink and watercolor. Towards the end I worked on images of the last agonizing weeks and days. I imagined the isolation and loneliness and finally being released from pain. I think these pieces were about her own release and acceptance as well as my own release.

For another art and grief article, read Mary J Luquette's story.

Return from Art and Grief to Journey through Grief homepage